An intimate look at two Syrian refugee families – images from photographer Giles Duley – by Rebekah Barnett

Life — and love — in limbo, as captured in these beautiful, poignant images from photographer Giles Duley.

Photographer Giles Duley (TEDxExeter Talk: The power of a story) has dedicated himself to documenting the long-term impact of conflict on civilians with his project Legacy of War. A few years ago, in partnership with the UNHCR, the UN’s refugee agency, he set out to cover displaced families, focusing on Syrian refugees. While he spent time photographing the Middle East-to-Europe odyssey that many refugees undertake, he decided he also wanted to highlight the less-documented lives of those in camps and settlements in Lebanon and Jordan. “What’s really difficult for refugees is the days, the months, the years of banality, of nothing happening,” he says. “That’s what I’m interested in, because that really is where their lives are.”

Duley, who was born in London, visited the settlements in the winter of 2016, taking intimate photos of a few refugee families. He chose his subjects the same way he chooses his friends — going with the people he immediately engaged with — and that’s exactly what these Syrians have become to him. “My only hope is that viewers can start to see them as families, as individuals, who have the same hopes and dreams as any one of us,” he says. Here, he shares the stories of two families.

Grounded by optimism and faith

In 2012, Khouloud (here, with her daughter Aya) was tending to the garden at home in Mo’damiyat al Sham, a city just south of Damascus, when she was shot in the spine by a sniper. She was left paralyzed from the neck down, and doctors gave her little chance of survival. She received medical treatment in Damascus, but as the situation in Syria became increasingly dangerous, she and her family — her husband, Jamal, and their four children — moved to Lebanon. Since then, they’ve been living in a makeshift shelter in an informal settlement of refugees in the Bekaa Valley. Made from a cardboard-like material and wood, the residence consists of a kitchen and a bedroom. It has no ventilation or heat in a valley where it can be cold enough to snow in the winter. As a tetraplegic, Khouloud cannot leave her bed, a situation that Duley can empathize with — after stepping on an IED in Afghanistan in 2011, he lost his left arm and both legs. Despite her situation, Khouloud “is the most positive person I know,” says the photographer. “She is funny, warm and has a faith that she believes everything will work out for her.”

Love in the face of adversity

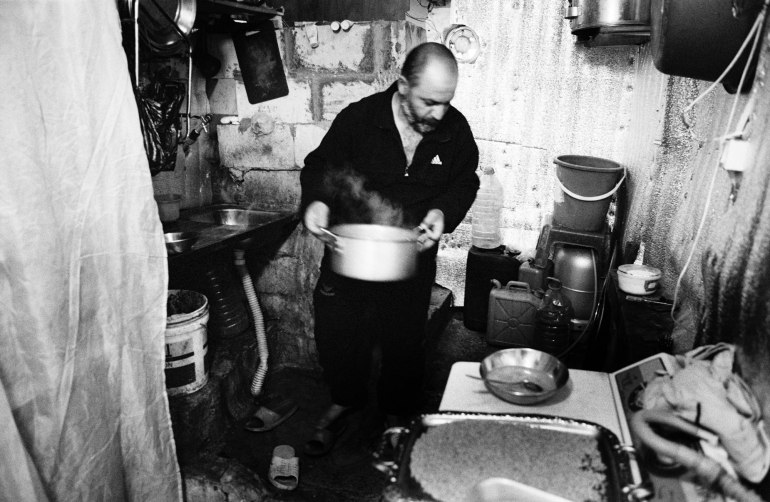

While most tetraplegics require full-time medical support, Khouloud has only her husband, Jamal, as her caregiver. Unlike many informal settlements, theirs has a school, which is where the family’s children spend their days. Jamal rarely leaves Khouloud’s side, because he doesn’t want her to be alone. When he is in the kitchen, Jamal — whom Duley describes as a “great cook” — periodically carries over spoonfuls of the meal for his wife to taste in the bedroom. Sometimes, she’d tell him the food needed more salt or pepper, but after he’d leave, Khouloud would wink at Duley, saying, “I just have to make sure he doesn’t know it’s perfect yet.” That interaction, says the photographer, is a perfect example of the affection and humor that exist between husband and wife.

The strength of family

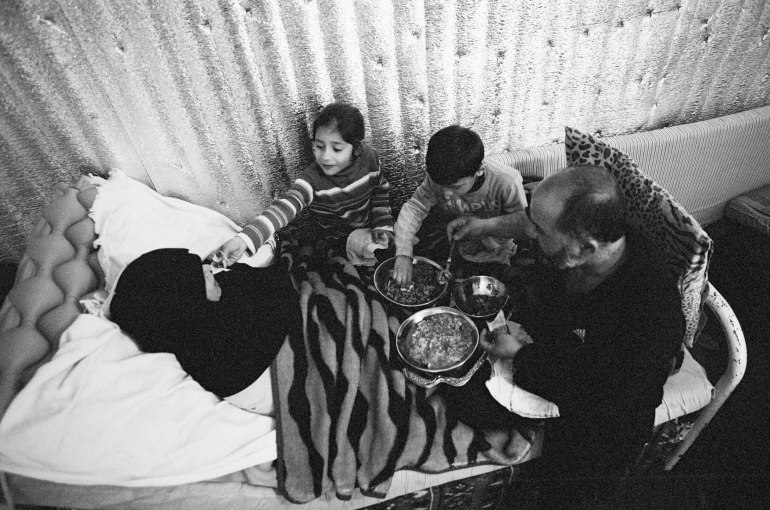

“Everyone is always helping Khouloud eat, and there’s always laughter,” says Giles of mealtimes in their home. Despite the family’s closeness, though, Khouloud occasionally has doubts, worrying she can no longer be a good mother due to her injury. Yet her children are at the top of their class at school, and Duley reminds her it’s “because of what you do with them and the love that’s in this house.”

Help, no matter how small, matters

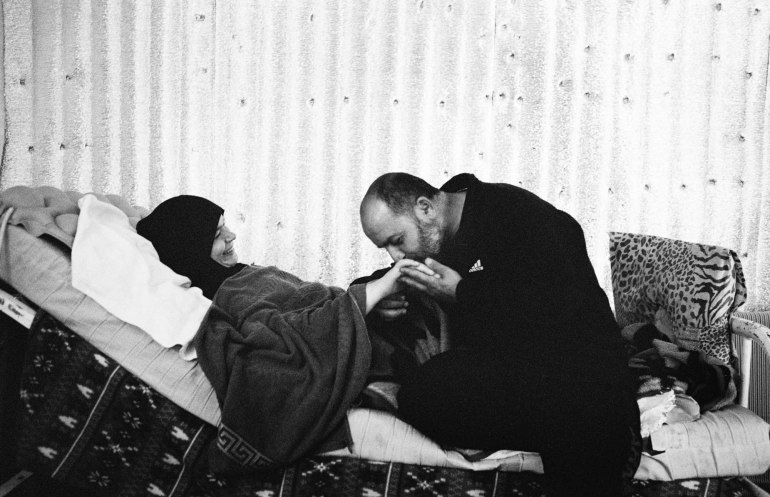

In this image, Jamal is shown massaging Khouloud’s feet and hands to help with her poor circulation. “Being the romantic he is, he always kisses her hands when he’s finished massaging her,” says Duley. In February 2017, the family learned they’d be moving into a real home in Lebanon as the result of a crowdfunding campaign that raised enough money to pay for the apartment (complete with garden), Khouloud’s medical treatment — and 10 years of expenses for the couple and their children. Even small contributions make an enormous difference to families like these, says Duley. “Maybe we can’t solve the whole crisis on our own. We can’t stop what’s going on, but working together we can still change the lives of these refugees.” Even though the family’s situation has improved dramatically, the photographer cautions they’re still caught in limbo, unable to fully move forward with their lives.

A need for speed

Aya (in the wheelchair) was born with spina bifida, a birth defect in which the spine does not close all the way. Although doctors expected her to live for just two months, she has defied their expectations and grown into what Duley calls “a little dynamo of energy and life.” Here, Aya, age 7, is being pushed in her wheelchair by her brother at top speed. “She loves to go as fast as physically possible in that wheelchair,” Duley says, “and here she is just screaming, ‘Go faster, donkey!’” The family — Aya and her four siblings and their parents — left their home in Idlib, Syria, in 2014 and moved to an informal settlement outside Tripoli in Lebanon. When Duley met them there, they told him they wanted to stay close to Syria. Within a couple of years, they’d reconsidered because they wanted Aya to get medical care, and the family was put forward by the UNHCR for resettlement in Europe. With no end in sight of the brutal conflict, Duley says he’s noticed a similar change of heart in many refugees: “Increasingly, people started to say to me that Syria was dead.” With schools, hospitals, and homes destroyed, the Syria they knew has become in some way permanently out of reach.

Life, in many ways, goes on

Formerly a kindergarten teacher, Aya’s mother, Sihan (right, sitting with a neighbor), became a community leader in her settlement, helping her neighbors solve problems. “This is something I’ve seen again and again in all the settlements I’ve visited in Lebanon — people trying to support each other and coming up with answers together,” says Duley. The concerns of the people there include running out of food and money, and, as is the case for Aya’s family, being unable to get medical treatment. Here, Aya’s mother and the neighbor discuss a problem that’s common to parents everywhere — the children were playing outside too late and making too much noise.

A double burden

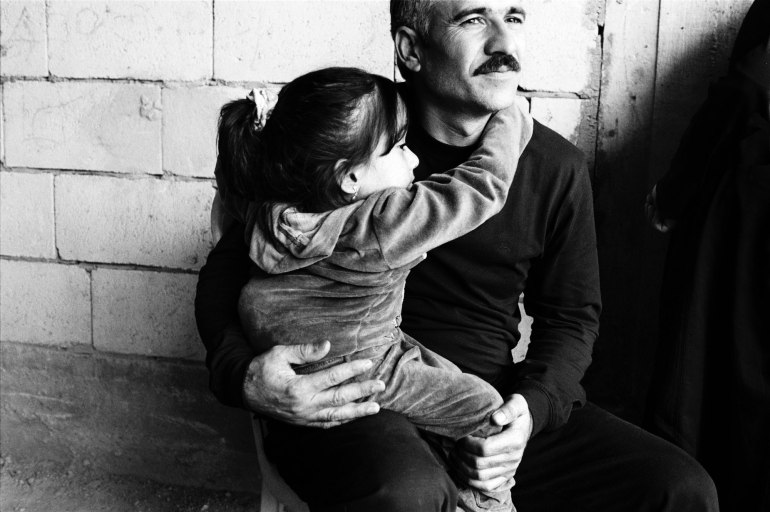

Here, Aya and her father, Ayman, who owned a soap factory in Syria, share a moment of closeness. While the uncertainty and inability to meet their children’s needs are difficult for both parents, Duley says it can take an extra toll on the men. While many of the women care for their families in the settlements, just as they did at home in Syria, the men are unable to find legal employment in Lebanon. “They’re really disempowered, because they want to be out working,” says Duley. “They feel their job is to support the family, and if they can’t do that, they feel like they’re failures.”

After more than a year of intensive background checks by the authorities, Aya’s family learned they’d been accepted for resettlement in France. Each family member was allowed to bring one suitcase. Sihan filled hers with Arabic coffee, and familiar spices like cumin and thyme. “I just want to make sure I have a taste of home when I get there,” she told Duley.

The taste of a new land

Here, the family prepares dinner in the kitchen of their new apartment in Laval, France, a few days after arriving in June 2016. Duley joined them for the meal. After helping the family pack in Lebanon, he’d flown ahead to France so he could greet them when they arrived and ease their transition. The family was given a pack of food by a French organization, and Sihan showed Duley a loaf of French bread and asked him what it was. When he told her it was bread, the entire family laughed: “That’s not bread! That’s not bread!” Duley says, “It’s almost impossible to believe what a culture shock, what a huge change it is.” But the parents were willing to endure it so their children could receive a good education and health care.

The gift of education

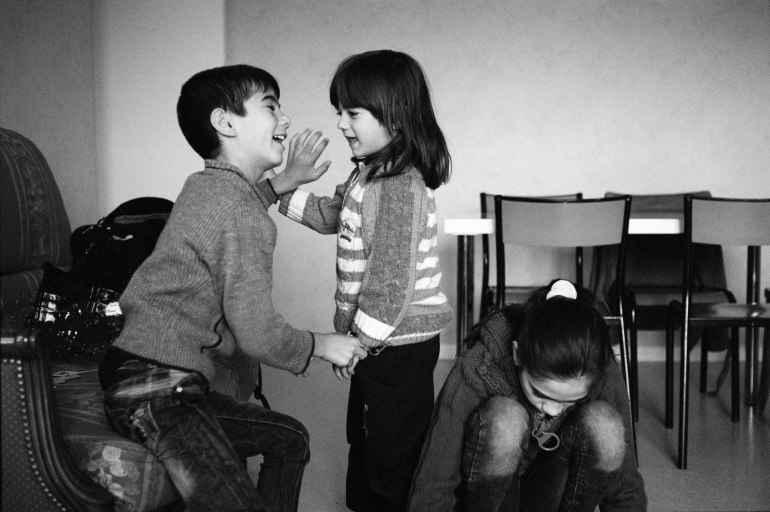

In France, Sihan’s children were enrolled in school again, something all refugee families are desperate to do, says Duley. While in Lebanon, the children could not attend school because the family couldn’t afford the bus fare to go there, so Sihan held classes in their tent for some of the kids in the settlement. The lack of formal instruction for refugee children is troubling. “This generation of Aya’s brothers and sisters, these are the people that the world will look upon to rebuild Syria, and they’re missing out on their education,” Duley says. In France, the gregarious Aya has been able to attend school for the first time, and she has made many friends. “They’ve been really, really welcomed there,” the photographer says. Sihan would like to get involved with the community in some way, perhaps helping other refugee families get settled, and Ayman will look for a job after he learns French.

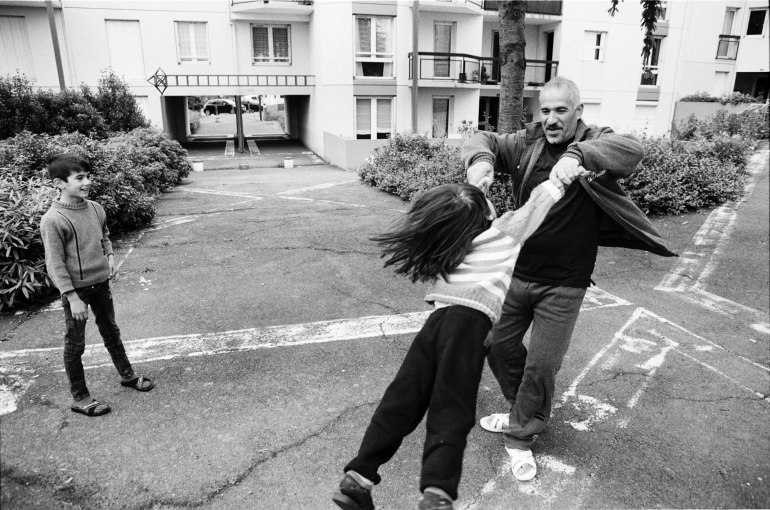

Childhood, rediscovered

The family can now play outside with a sense of freedom and safety they hadn’t experienced for years. In Syria, one of the children saw a friend shot outside her window. “These kids have suffered unimaginable horrors, and although they’re incredibly resilient, without hope and without future, those things start to fester,” says Duley. “For them to be in France was an opportunity to be kids again and to start all over.” But they continued to carry deep scars from the trauma. Sometimes, a plane flying overhead was enough to make the children run for cover. Still, in France, Duley finally saw Ayman and Sihan smile wholeheartedly for the first time. “It’s like a weight has been lifted off them,” he reflects.

As for Duley, he believes working with Khouloud and Aya has saved his life. After being injured in Afghanistan, he was told he’d never work or walk again, a devastating diagnosis that he overcame with difficulty. Work was slow in the beginning of his recovery, and during a lull, he arranged a trip with Handicap International, a nonprofit which supports people with disabilities in conflict and disaster zones, which is how he met Aya. Over the years, he’s been able to advocate for Khouloud’s and Aya’s families, and, as he puts it, “at a time when I didn’t know if I had any point in doing my work, to be able to document their lives and to be able to change their lives in a small way made it feel like there was still worth to what I did.”

All photos are by Giles Duley/UNHCR.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rebekah Barnett is the community speaker coordinator at TED, and knows a good flag when she sees one.