Living in the Shadows, a Family Tries to Secure Its Children’s Future – by Abby Sewell

In the first of our in-depth reports on the education crisis for Syrian refugees, Abby Sewell reports from Lebanon on the challenges faced by Syrian siblings in a country with the highest per capita number of refugees in the world.

TEL ABBAS, LEBANON – In a one-room schoolhouse tucked amid the tents in an informal refugee camp in northern Lebanon, a pair of volunteers were trying to keep about 20 squirming Syrian children focused on a French lesson.

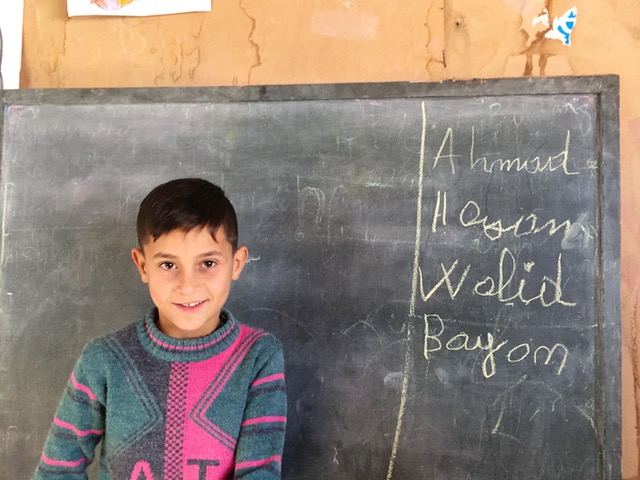

Ahmad, seven years old, has struggled with French in his Lebanese school. Abby Sewell

Ahmad, seven years old, has struggled with French in his Lebanese school. Abby Sewell

“Ahmad, quel âge as-tu?” (“Ahmad, how old are you?”)15

Uncomprehending, a seven-year-old boy with alert eyes and a shock of straight, black hair falling over his forehead summoned the one phrase of French he had committed to memory: “Je m’appelle Ahmad.” (“My name is Ahmad.”)

Ahmad was never abashed about shouting out an answer, even though it was often wrong. The third from youngest in a family of nine children, he was always competing for attention.

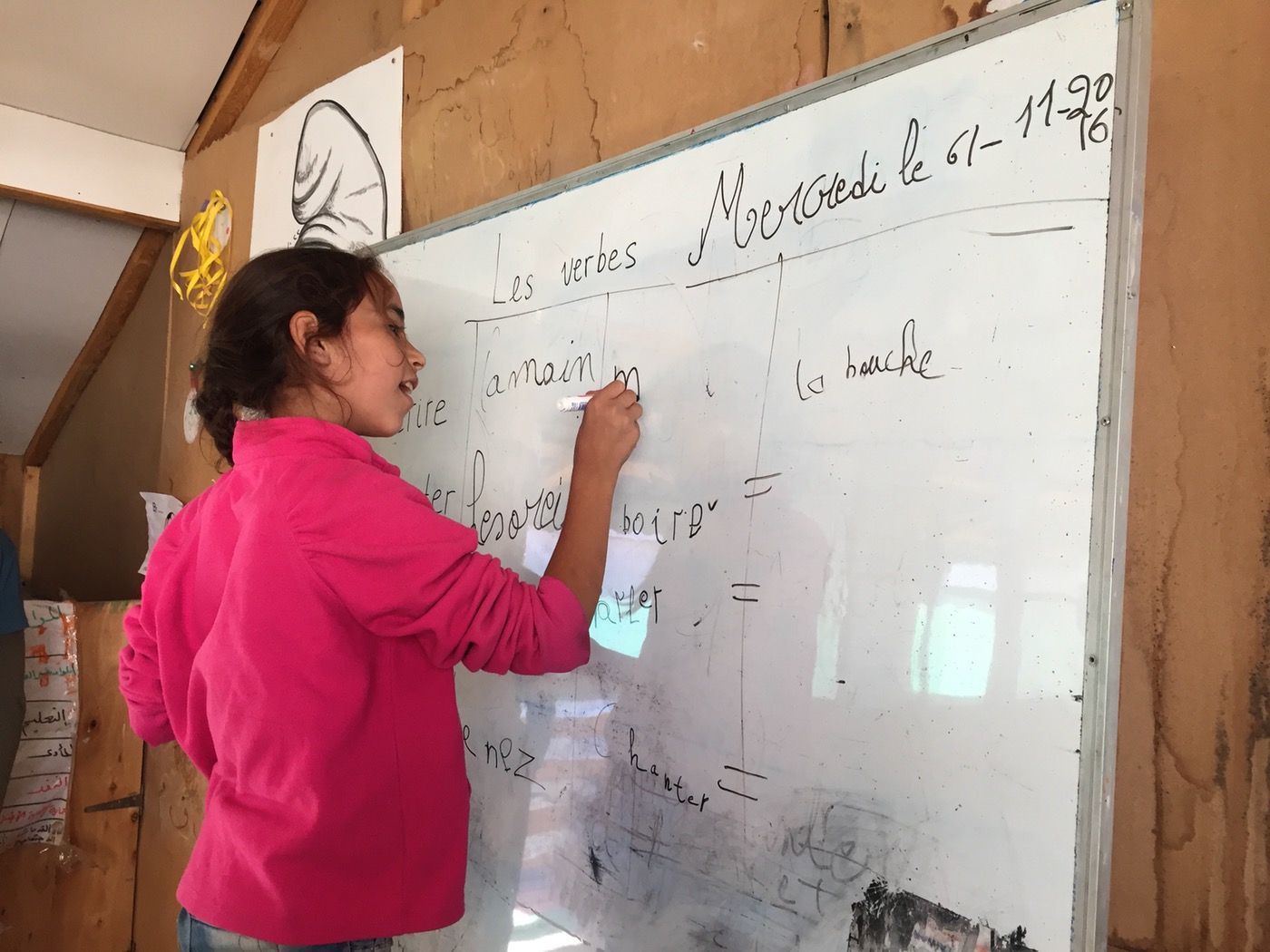

While Ahmad struggled, his nine-year-old sister Ghoufran, and 12-year-old brother, Abdel Rezaq, were already bored with the lesson but happy to show off their more advanced knowledge.

“J’ai neuf ans,” Ghoufran said promptly.

“J’ai douze ans,” said Abdel Rezaq.

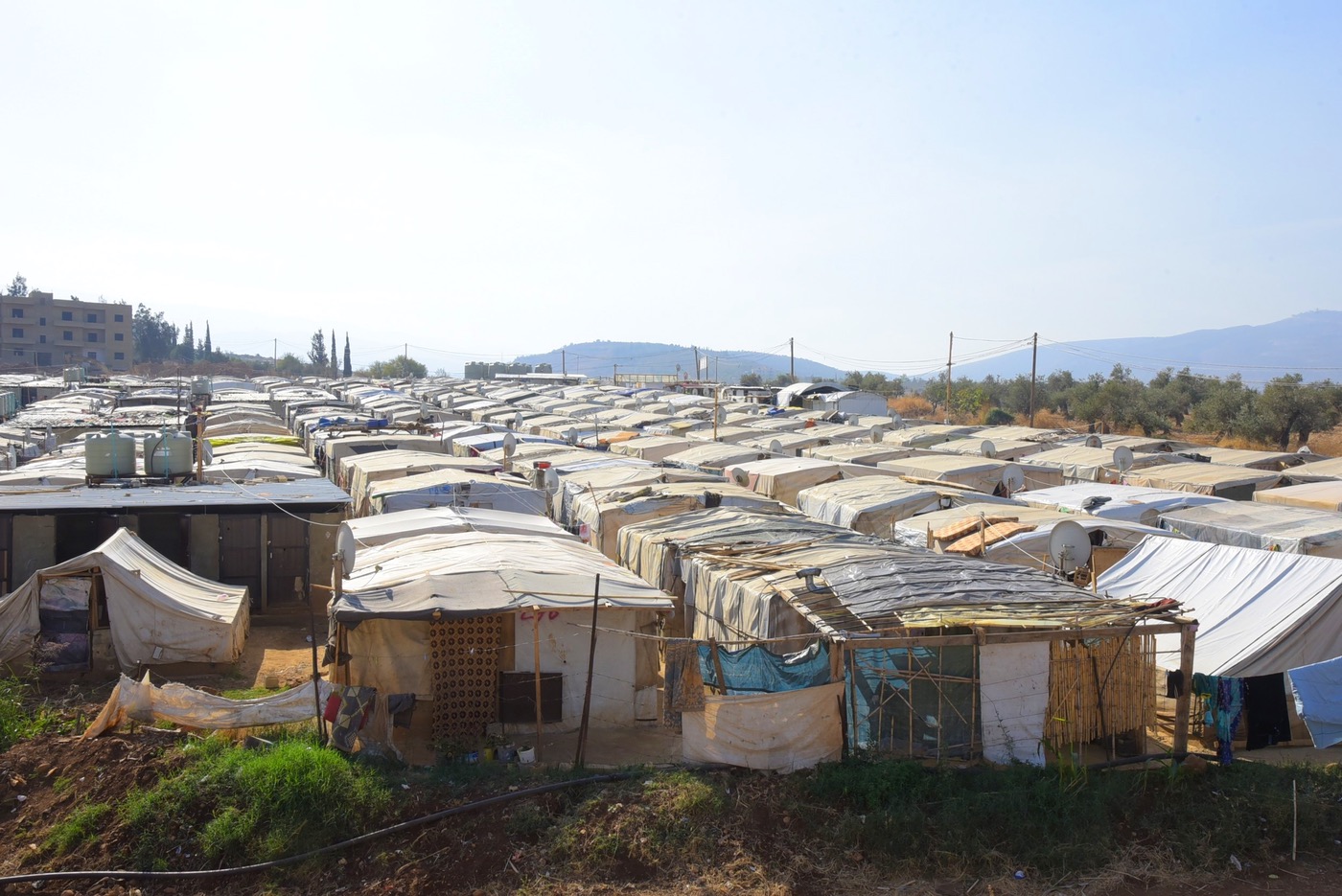

The family fled the fighting in Aleppo four years earlier and landed in this makeshift settlement on a dusty road in Tel Abbas, a small municipality on the outskirts of the Lebanese city of Halba. They share a United Nations-provided tent in the encampment of 25 families, one of about 4,000 informal refugee camps in Lebanon.

Even if they wanted to go back to Syria, their house there has been destroyed by bombing. The family had pinned their hopes on one day finding a way to Europe.

But for now, they were stuck in Lebanon, and some of the siblings were struggling to adjust to the more arcane aspects of the Lebanese public education system, which required them to learn subjects including math and science in French rather than their native Arabic, a legacy of Lebanon’s colonial history.

Still, being in school at all was a victory of sorts.

In the first year after they arrived in Lebanon, none of the children went to school, said their father, Ali Muhammad al-Abdullah – or Abu Abdullah, as everyone calls him. There was no public school that was willing or had room to accept them, and the family could not afford private education.

The Second Shift

In the first years of the war in Syria, refugee children in Lebanon had little access to education, except for some informal camp schools and other programs run by NGOs or community organizations.

“Everyone here thought they would go back in two or three months or tomorrow,” said Katya Marino, chief of education for the U.N. children’s fund (UNICEF) in Lebanon. “Nobody at that point was thinking we would be in a situation where the children are now entering their sixth year here in some cases.”

The Lebanese public school system was suffering from anemic enrollment, as the majority of Lebanese children attend private schools. Even so, there was still not enough room to accommodate the number of children fleeing from Syria.

In 2013, as the war showed no sign of abating, Lebanon opened up a “second shift” of classes in the afternoons for refugees. It was the country’s eventual answer to the ballooning population of Syrian refugees – now more than 1 million, including about 550,000 children up to the age of 18 and 280,770 aged six to 14, for whom education is compulsory.

Ahmad, Ghoufran and Abdel Rezaq eventually found spots in their local public school’s second shift.

Ghoufran picked up French easily and flourished in her new school. For Abdel Rezaq, who began his education in Syria before the war and hopes to be a doctor one day, the language barrier made his favorite subjects an ordeal.

“Science is beautiful, but French, no,” he said. “I like to learn, but the schools here are not good.”

Ahmad, easily distracted, remained thoroughly confused by French. Despite constant drills, he could barely recognize the letters of the Latin alphabet, and his parents, who speak only Arabic, could not help him.

Ghoufran, nine years old, has flourished at school in Lebanon. She is quick to shout out a correct answer or volunteer to write out sentences on the board in carefully practiced cursive script. (Abby Sewell)

‘Slow Decline’

The children had joined a public school system already under strain.

The Lebanese ministry of education, in a report released last year on its plans for addressing the refugee crisis, noted that the country’s public schools were plagued by “dated approaches to pedagogy, unfavourable allocation of public resources … low investment into education infrastructure and premises” and had been in “slow decline” for years.

Nevertheless, Marino said, the Lebanese public school system offered important advantages over other options for refugee education.

“We were using a system that was already in place, which makes a big difference in a crisis,” she said. And unlike the various informal options, the public school system gave children a chance to earn a certificate that would open the possibility of continuing to higher education and allow them to more easily continue their formal education in Syria if they returned.

As of January, there were about 195,000 non-Lebanese children – nearly all Syrian – enrolled in Lebanese public primary schools, narrowly outnumbering the Lebanese students.

About 65,000 of them enrolled in the first shift with Lebanese students, where some Syrian children were bullied by their Lebanese classmates, Marino said. The majority attend second-shift classes reserved for refugees only.

At the public schools attended by the al-Abdullah children, there were sometimes shortages in materials. The children didn’t receive their textbooks until a month after the school year had started. Teachers who also taught in the morning first shift were already tired by the time the Syrian children arrived. Sometimes the children fought and some of the teachers hit the students when they misbehaved.

Still, al-Abdullah said, “Any school is better than nothing, of course.”

Benefits of Integration

The Syrian refugee crisis has hit Lebanon particularly hard. The small country now hosts the highest number of refugees per capita in the world. Syrian refugees are often cited as a strain on its dysfunctional public services. Lebanese politicians continually insist that refugees must return to Syria, and soon.

Yet institutions like the Ministry of Education have received much praise from international organizations for their effort to educate Syrian children, regardless of their legal status in the country.

Since the early days of the Syrian crisis, Lebanon has seen a significant increase in refugee enrolment. In 2015, the U.N. found just over half of Syrian children aged between six and 14 in Lebanon were attending any sort of school. Now, about two-thirds of Syrian children in Lebanon in the compulsory school age group attend public schools, according to statistics provided by UNICEF and the Ministry of Education.

Not far from Tel Abbas, the larger Reyhanli refugee camp in Akkar, pictured on November 11, 2016, has housed hundreds of refugees. (Muhammed Salih/Anadolu Agency)

Sonia Khoury, who is in charge of the education programs for Syrians at the Lebanese Ministry of Education and Higher Education, said it made sense to integrate the Syrian children into the Lebanese system because the curricula of the two countries were similar.

“Their future is to go back to their own country and rebuild their own country and we don’t want the years that they have spent here to be useless.”

“Their future is to go back to their own country and rebuild their own country and we don’t want the years that they have spent here to be useless,” she said.

In the long term, some analysts hope that refugees could benefit Lebanon’s ailing public school system. Investment in updating the Lebanese curriculum and school infrastructure because of the Syrian crisis could result in better schools for the Lebanese.

On the other hand, Khoury said education officials worried that the international funding would dry up before the improvements could be carried out.

“If next year Syria is not any more at war and they want to rebuild Syria, the focus of donations and construction will be on Syria,” she said. “But the kids will stay here until everything is normal back in Syria, so how will we educate them?”

The School Bus

Some Syrian families have found ways to supplement or replace the public school system by sending their children to private schools or informal ones run by NGOs and religious organizations, including some that teach the Syrian rather than Lebanese curriculum.

Struggling with French, Ahmad, along with some of his siblings, started attending morning classes in a small informal schoolhouse in the Tel Abbas camp organized by a small Belgium-based NGO called Relief &Reconciliation for Syria. International volunteers, and now a part-time Lebanese teacher, came to deliver remedial French lessons and help the children with their homework several mornings a week.

After the classes, the children wait in front of the camp for a bus to take them to public schools in Halba and neighboring towns for the second shift. Transport has been a barrier to refugees’ access to schools in many areas of Lebanon, as many of the refugee settlements are in remote and rural areas.

The bus has also been a sore point with some of the families in the camp. UNICEF gives them $20 a month for each child aged under 10 enrolled in school and $65 for the older ones – to cover transport costs and help replace the income lost by older children not working.

But the bus drivers, who knew how much aid the families were getting, always set the price at exactly that amount, al-Abdullah said, so there was never any left over.

Going to Work

For all the success of Lebanon’s push to expand refugee enrollment, it did not reach everyone. Only about 3,000 non-Lebanese students were enrolled in secondary schools as of January. Even among younger children, the dropout rate has been high. In 2015, the U.N. found that less than half of Syrian children who entered first grade in Lebanon made it to grade six.

Khoury, the ministry official, acknowledged the problem of keeping older children in education. “They are working, very simple,” she said. “They cannot afford to lose their day and go to school.”

A Syrian child sells tissues for drivers in Beirut, Lebanon, May 28, 2016. (AP/Bilal Hussein)

Child labor was already a problem in Lebanon before the refugee crisis, and has increased since the Syrian war. In part, that is because of the shaky legal status of many of the children’s parents.

Refugees, in most cases, are not allowed to work in Lebanon. Many found informal jobs, but since the government introduced new residency regulations in 2015 many refugees have been unable to obtain or renew their permits, leaving them without legal status. While Lebanese authorities recently announced a waiver of the $200 annual residency fee for most refugees, the effect of the policy remains to be seen.

“Any trip outside the camp means risking arrest at a checkpoint. Children are better able to get around undetected”

In the meantime, for most refugees, like the al-Abdallah family, any trip outside the camp means risking arrest at a checkpoint. Children are better able to get around undetected.

When the family arrived in Lebanon, four of Ahmad’s older brothers went to work. They never returned to school.

The eldest, Abdullah, now 21, had planned to continue his studies in Lebanon. But “when we came here, there was no food in the house,” he said. “I needed to work.”

He and his brothers did construction jobs, seasonal work on the potato and olive harvests and whatever other odd jobs they could find.

But the work has dried up for Abdullah, who does not have a valid residency permit. He passes the time coaching kids from the camps in soccer and helping with the remedial classes. He is trying to teach himself English from a lesson book written for native Arabic speakers.

The second eldest son, 18-year-old Mohammed, looks younger and can still travel without attracting attention from the authorities. For the past few months, he has worked at a construction site in a Beirut suburb, sleeping in the half-finished building during the week and returning north to visit his family on the weekends.

“I was forced to leave my school due to this goddamned war,” he said. “Now I am in my fourth year as a refugee, working the hardest jobs away from my family, my school and my future.”

Before the war, Mohammed had big ambitions. Maybe he would become a doctor, or an engineer or a teacher; any of it seemed possible. Now his options have narrowed. “Work, sleep. Work, sleep,” he wrote on Facebook. “I miss myself.”

If the family stays in Lebanon, the younger children will probably also drop out of school early. “After two years, I will have to go to work, too,” Abdel Rezaq, the 12-year-old aspiring doctor, said matter-of-factly.

The children’s father is hoping for an end to the war, or resettlement in another country where the children will have better prospects.

“The most important thing is to have education. It’s very important if there’s going to be a future,” al-Abdullah said. “But if we stay here, there is no future.”

The author of this story, Abby Sewell, volunteered for Relief & Reconciliation for Syria in Tel Abbas from October to December 2016.

Never miss an update. Sign up here for our Syria Deeply newsletter to receive weekly updates, special reports and featured insights on one of the most critical issues of our time.

About the Author

Abby Sewell

Abby Sewell is a freelance journalist based in Lebanon and former staff writer for the Los Angeles Times. Her work has focused on criminal justice, mental health and now refugee and development issues. Follow her on Twitter at @sewella.