Trapped in a Town Under Siege: Syrian Children Are Eating Leaves to Survive By Zack Baddorf

When she was brought to a field hospital in rebel-held Moadamia, one mile north of Damascus, Syria’s capital, Rana Obaid had all the signs of severe malnutrition—a bloated belly, glassy eyes, hollow cheeks, and bloodied gums. Doctors examined her but there was little they could do.

The one-year-old died within a day. Cause of death: starvation.

After he viewed the videos, Dr. Maher Nana told me he had noticed bleeding in the child’s gums, which is typical of Vitamin C deficiency. “To reach this point of Vitamin C deficiency, you need to be in a deep, profound malnutrition,” explained Dr. Nana, a Syrian American who runs a family practice in Florida and who travels regularly to Syria.

“You really have to be not eating anything,” he said.

Rana wasn’t the first Syrian child to die of hunger in Moadamia. A seven-year-old girl died due to malnutrition on Friday. Three other children (aged three, five, and seven) and two women (aged 34 and 48) also slowly starved to death, because Syrian President Bashar al Assad’s military and regime-backed militias had besieged the town.

Duaa al Sheikh, a 7-year-old Syrian girl in Moadamia, died due to malnutrition on Friday.

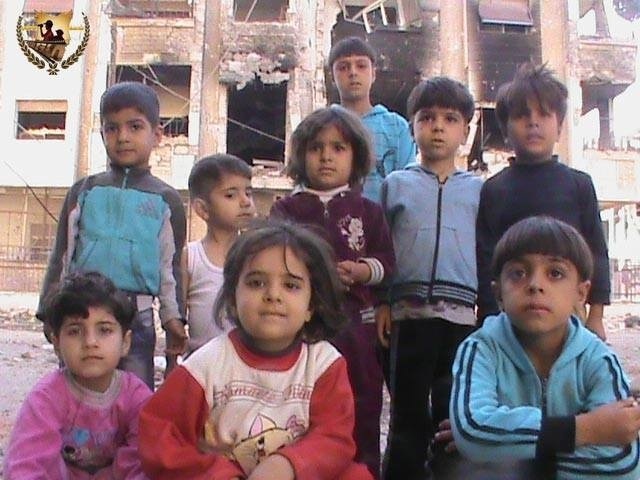

Back in mid-August, the town fell victim to the Sarin nerve-gas chemical attack by the Assad regime. Over the past year, the town’s population has dropped from 70,000 to 12,000. Most had fled, but the remaining residents have no way to leave. More than half are women and children, according to the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces.

Anyone who tries to leave “gets shot or tortured to death,” Moadamia resident, Dani al Qappani told me over Skype that regime snipers will shoot people if they attempt to leave the town.

For nearly a year, the town has been under siege, meaning no food or medical supplies have been brought in, not even through humanitarian aid agencies. Bread supplies ran out more than six months ago.

The residents eat just whatever they can grow—olives, figs, berries, pomegranates, and foliage like grape leaves.

“It’s just something to keep them alive basically,” Dr. Nana said. “The leaves that you eat have no nutrition. It’s empty. It’s just to fill their stomachs.”

Moadamia resident and field hospital physician, Dr. Omar Hakeem, told me there’s “widespread hunger” in the town.

“Our children are dying between our hands one by one, not because of the bombing,” 26-year-old Dani said.

But there is bombing, too.

In addition to the daily battles between regime and opposition troops, the town is also under near constant regime attack by shelling. I heard shells exploding in the background over Skype while I interviewed the Moadamia natives. Dani apologized for the delay, “I am so, so sorry,” he said. “There is heavy shelling.”

Once the shelling subsided, Dani continued: “One year under siege. One year under heavy shelling. One year and our blood is being shed. We don’t fear death anymore.”

The opposition estimates about 700 people were killed there.

“People live most of their time in shelters because of shelling from artillery and rocket launchers,” Dr. Hakeem said.

Electricity has been out for a year.

Children don’t go to school, because the schools are either “destroyed or deserted due to heavy shelling,” according to Dani. The town’s field hospital has ran out of almost everything. When people are sick, they take painkillers.

“Few people take the risk of walking in the streets,” Dani said. “The regime kills us daily and no one cares. The streets are empty. The shelling never stops.”

Life is a “disaster,” he said. Hakeem described the siege as “genocide.”

Regime jet fighters bombed Moadamia three times on Tuesday, killing two people, injuring ten others, and destroying one of the two remaining water pipes, according to Qusai Zakarya, a spokesperson for the local city council in Moadamia.

“The people here are determined to defend their land and their homes until the last drop of blood,” Hakeem, 26, said that he has been physically weakened and exhausted from treating the chemical-weapons victims.

Dani feels that dying from starvation is the worst way to die, a “slow death.”

Dani recorded a video of a mother with her malnourished child. When he asked her why the child is malnourished, she replied, “I have nothing left—nothing to feed him and no milk.” The mother said she makes soup for him if she can find some. Otherwise, she explained, “Water does the job.”

he number of deaths due to starvation may rise soon, Dr. Hakeem said. In his field hospital, 15 children are now in intensive care—all at risk of death from malnutrition.

A simple fix would be milk.

Milk contains all the electrolytes, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, and other elements essential for human survival, Hakeem said. “Women can produce milk, even if they are malnourished, [but] some women cannot produce milk at all,” said Dr. Nana. “In this case, there’s no alternative, no other way” to feed the children because no cow milk or artificial milk are left in town.

The UN’s humanitarian chief, Valerie Amos, confirmed that the UN has been unable to deliver supplies to the town for nearly a year, “despite repeated attempts, due to security constraints.”

“Civilians continue to be targeted or denied access to food and emergency medical treatment in many places across Syria in this horrendous crisis,” she said in a statement. “I call on all parties to agree a pause in hostilities to allow humanitarian agencies immediate and unhindered access to evacuate the wounded and provide life-saving treatment and supplies in areas where fighting is ongoing.”

The Syrian government would have to grant the UN’s World Food Programme permission before it can provide aid in Moadamia.

“Our food is ready,” said Abeer Etefa, WFP’s senior spokesperson for the Middle East. “We’re always ready and we take any opportunity, no matter how small it is… to get to the people in need.”

Abeer spoke to me over the phone from her office in Cairo. “[WFP] is a humanitarian org,” she said. “We can only appeal. We can only request access. We can only push and request permissions to go [provide aid]. At that point, our mandate stops.”

Amos emphasized that both the Syrian government and the rebels have an obligation under international human rights and international humanitarian law to protect civilians and “allow neutral, impartial humanitarian organizations safe access to all people in need.”

Nearly a year into the Moadamia siege, there’s been limited progress.

“There are no ongoing talks on a ceasefire,” Khalid Saleh, the opposition coalition’s media director, told me. “The Assad regime offered the Free Syrian Army to allow humanitarian aid in, if they drop their weapons and withdraw from the suburbs of Damascus. However this means Assad forces will take over the area, so, of course, they did not agree.”

On Saturday, the regime permitted the Red Cross and the Red Crescent to evacuate about 1,000 women, elderly and children from Moadamia. They are being held at a school, according to Zakarya. The coalition alleges that ten boys evacuated in the group were kidnapped. They report that four of these boys were released after being tortured “while undergoing intense questioning” about rebel forces in Moadamia.

Moadamia is not the only town under siege. About 2 million people in rebel-held areas near Damascus are trapped by regime forces and can’t get outside aid.

The opposition has been asking international aid agencies and a variety of international leaders, including US Secretary of State John Kerry, to pressure the Syrian regime to create humanitarian corridors that would permit food and medicine to be transferred into the besieged areas.

“Promises to help were made but nothing happened yet, as usual,” Khalid said.

Khalid told me Russia could change the situation. “The Russians have proven they can apply pressure on the regime successfully, when it matters,” he said.

Assad is sending a message to Syrians supporting the revolution, Khalid said. “Whether he’s using chemical weapons or using starvation as a force, he’s saying, ‘I own you and I can do whatever I want,’” Khalid said, “and the international community will do nothing about it.’”

Syrian government officials at the Washington embassy declined to comment for this story.

For residents of Moadamia, the situation is “only getting worse and worse,” according to Zakarya.

Syrians are “very, very disappointed” with the United States, Zakarya told me. “We were expecting from the government of the United States and the people of the United States … that they are going to support [us] helpless people after three brutal years of killing by this fascist man, Bashar al Assad.”

“The United States and the Western World wasted a golden opportunity to win the hearts of the Syrians,” he continued. “Now people are feeling furious and angry from just mentioning the name of the United States.”

I asked Dani to follow up with Rana Obaid’s parents, but they refused to comment.

“It is useless,” they told Dani. “No one in this world would care for [our daughter’s] misery or our misery here in Moadamia.”