What’s Left of the Syrian Arab Army? Not much – by Tom Cooper

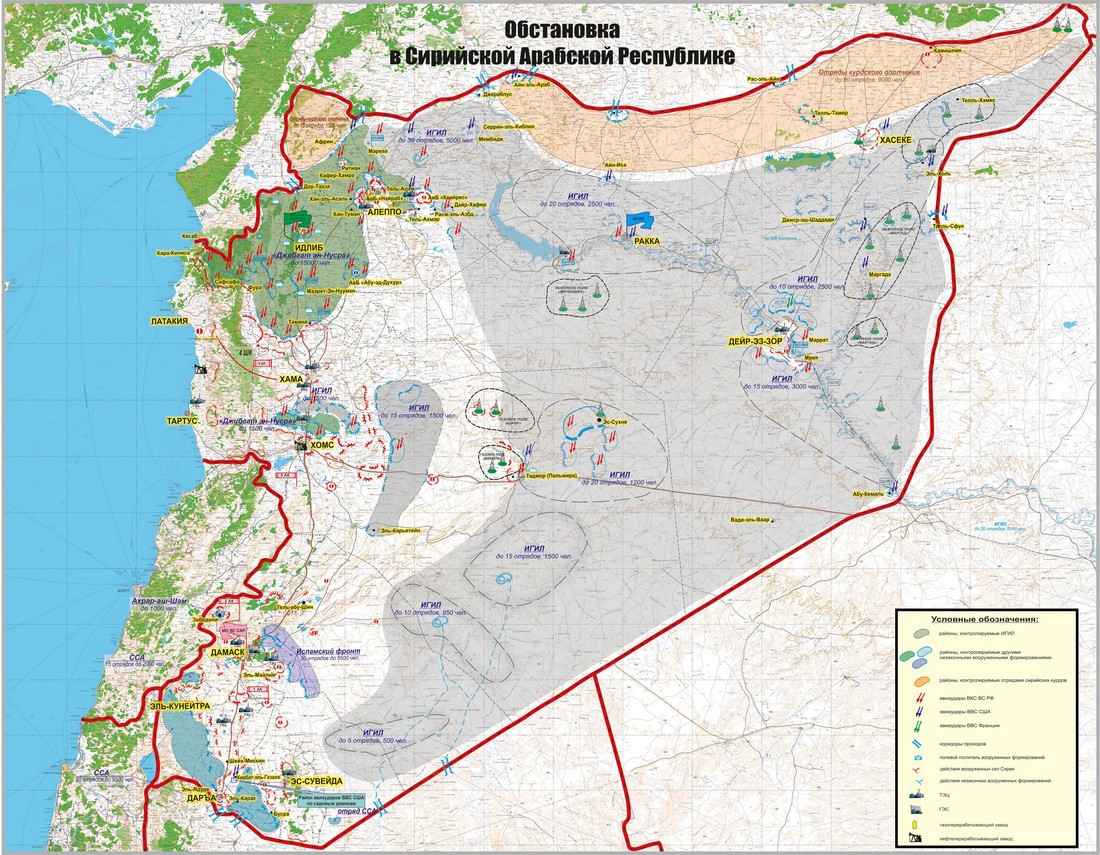

The general impression is that the Syrian Arab Army remains the largest military force involved in the Syrian Civil War, and that — together with the so-called National Defense Forces — it remains the dominant military service under the control of government of Pres. Bashar Al Assad.

Media that are at least sympathetic to the Al-Assad regime remain insistent in presenting the image of the “SAA fighting on all front lines” — only sometimes supported by the NDF and, less often, by “allies.”

The devil is in the details, as some say. Indeed, a closer examination of facts on the ground reveals an entirely different picture. The SAA and NDF are nearly extinct.

Because of draft-avoidance and defections — and because Al Assad’s regime was skeptical of the loyalty of the majority of its military units — the SAA never managed to fully mobilize.

Not one of around 20 divisions it used to have has ever managed to deploy more than one-third of its nominal strength on the battlefield. The resulting 20 brigade-size task forces — each between 2,000- and 4,000-strong — were then further hit by several waves of mass defections, but also extensive losses caused by the incompetence of their commanders.

Unsurprisingly, the regime was already critically short of troops by summer of 2012, when advisers from the Qods Force of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps concluded that units organized along religious and political lines had proven more effective in combat than the rest of the Syrian military had.

Thus the regime’s creation, in cooperation with Iran, of the National Defense Forces. Officially, the NDF is a pro-government militia acting as a part-time volunteer reserve component of the military. Envisioned by its Iranian creators as an equivalent to the IRGC’s Basiji Corps, the NDF became an instrument of formalizing the status of hundreds of “popular committees” created by the Syrian Ba’ath Party in the 1980s.

According to Iranian claims, the NDF’s stand-up resulted in the addition of a 100,000-strong auxiliary to Syria’s force-structure. Moreover, the NDF functioned as a catalyst for the reorganization of the entire Syrian military into a hodgepodge of sectarian militias.

Namely, the IRGC and various other domestic and foreign actors began sponsoring specific NDF battalions. These actors included the Ba’ath Party, the Syrian Socialist National Party (SSNP), groups of Palestinian refugees living in Syria for decades — such the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine — the General Command and the Palestine Liberation Army and even the Gozarto Protection Force, the latter made up of local Christian Assyrian/Syriac and some Armenian communities.

Strongly encouraging this process, the regime then went a step farther and authorized a number of businessmen and shadowy figures from Syria’s Alawite minority to create their own, private militias. All of these organizations offered much better salaries to their combatants than either the SAA or the NDF could, and thus proved an attractive alternative for thousands of Syrians.

At least as important is that most of organizations in question proved capable of deploying heavy weapons, too. A majority of the battalions of resulting militias each usually total around 400 combatants, often riding on a miscellany of so-called “technicals” — essentially four-wheel-drive trucks fitted with heavy machine guns or light automatic cannons — plus between three and 15 armored vehicles.

This process or reorganizing the Syrian military into a gaggle of sectarian militias was nearly complete by the time when Russians launched their military intervention in the country in the summer of 2015.

Correspondingly, while planning a counteroffensive against insurgents in northern Latakia, the Russians established what they call the “4th Assault Corps” — a typical formation for what can be considered the modern-day Syrian armed forces.

Leaning upon the command structure of the former 3rd and 4th Divisions of the SAA, this headquarter is exercising control over the 103rd Republican Guards Brigade and six brigades of Alawite militia, all of which are private military companies administrated by the Republican Guards.

The 4th Assault Corps also includes the Nusr Az Zawba’a Brigade of the SSNP and two brigades of the Ba’ath Party Militia, or BPM. Because these units lacked in firepower, they were reinforced by Russian army artillery batteries drawn from the 8th Artillery Regiment, the 120th Artillery Brigade, the 439th Guards Rocket Artillery Brigade and the 20th Rocket Regiment — the latter equipped with the TOS-1A.

To lessen the strain upon this force, four battalion-size task forces — drawn from the Russian 28th, 32nd, and the 34th Motor Rifle Brigades and the 810th Marines Brigade — secured the secondary lines and supply depots.

A similar organization was subsequently introduced in the Damascus area, too. Although the regime can still fall back on at least five brigades of the Republican Guards Division deployed there, these units are incapable of running offensive operations.

Therefore, major assaults on insurgent-held pockets in Damascus and eastern Ghouta are overseen by two brigades from the Lebanese Hezbollah, three brigades of the PLA and various of local IRGC surrogates, including the Syrian branch of Hezbollah.

Units of Iraqi Shi’a militias are not only securing the Sayyida Zaynab District of southern Homs, but have also deployed to fight Syrian insurgents, too. Furthermore, IRGC-controled units of Iraq’s Hezbollah branch, Hezbollah-Syria, the PFLP-GC and the PLA played a crucial role during the offensive that resulted in the capture of Sheikh Mishkin in January 2016.

Currently, Homs and Hama appear to be the last two governorates with any kind of significant concentration of the SAA. Actually, merely the HQs of various former SAA units are still wearing their official designations. Their battalions all consist of various sectarian militias — including that of the Ba’ath.

The latter played a prominent role in the creation of several “special forces” units renown for their offensive operations in eastern Homs and southern Aleppo. These include the “Tiger Force” and the “Leopard Force.”

Essentially, all are private military companies, financed by businessmen close to Al Assad. Their operations in the eastern Homs and Palmyra areas are supported by battalion-size elements of the Russian 61st Marine Brigade and the 74th Guards Motor Rifle Brigade.

Despite the presence of such units as the Ba’ath Commando Brigade, the city and province of Aleppo are largely controlled by Iranians, foremost the IRGC.

The latter is usually said to operate three or four units in Syria. Actually, the Fatimioun Brigade (staffed by Afghan Hazars) and the Zainabioun Brigade (staffed by Pakistani Shi’a) are most often cited, while the Pasdaran have deployed four other such formations in Aleppo province alone — all staffed by their own regulars.

Ironically, the IRGC’s fire brigade in this part of Syria is the Al Qods of the PLA Brigade. These units are supported by Russian army troops, too, including those from the 27th Guards Motor Rifle Brigade and the 7th Guards Assault Division and several artillery batteries.

Even larger are different contingents of Iraqi Shi’a, including nine brigade-size formations of Badhr and Sadrist movements, seven brigades of the Assaib Ahl Al Haq movement, five brigades of the Abu Fadhl Al Abbas movement, two brigades of the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Units and nine brigades staffed by Iraqi Sh’ia but which the author of this report was unable to associate with specific political movements in Iraq.

Finally, even the Islamic Republic of Iran Army is present in Syria, in the form of the 65th Airborne Brigade.

Correspondingly, there is hardly anything to be seen of the actual SAA and very little of the NDF. It’s unlikely that Al Assad has more than 70,000 troops left under his command.

On the contrary, while Iranians are said to have about 18,000 troops in Syria, considering the average size of the brigades they and Iraqi Shi’a are deploying there, they more likely to oversee at least 40,000 combatants.

On the top of this all, one should not ignore the Russian military presence, which is also larger than media usually report. In addition to the units listed above, Moscow’s forces include elements of no fewer than four Spetsnaz brigades — the 3rd, 16th, 22nd and 24th, primarily responsible for the Hmemmem and Sanobar air bases near Latakia and Shayrat air base in southeastern Homs.

All told, the Russians have at least 10,000 — and more likely up to 15,000 — troops in Syria.